I kind of miss H. Ross Perot. Whether you thought he would have made a good President or not, the man sure knew how to explain complicated issues to the public.

It’s also a bit strange for me to look back on this debate from 1992. I was only 12 years old at the time, but I followed politics even then along with my parents. Now, nearly 24 years later, we’re still debating many of the same issues we were debating back then.

Back in 1992, Perot described health care (he really meant employer-sponsored private health insurance) as “the most expensive single element” in making a car in the United States. And if he thought it was expensive then, just imagine what he would think now.

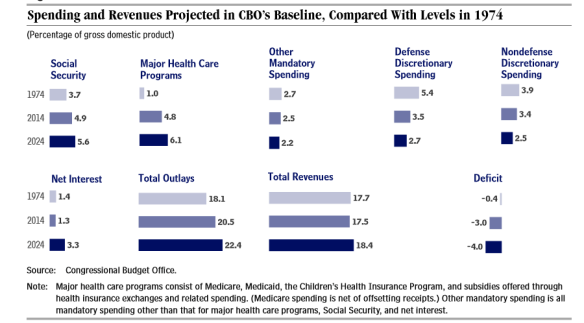

Health expenditures in the USA have grown considerably over the years as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In 1992, health expenditures accounted for just over 13 percent of GDP. In 2014, health expenditures accounted for 17.4 percent of GDP. Note: Percentage of GDP does not need to be adjusted for inflation or population growth…it’s a constant statistic.

It’s obvious that we’re spending a considerably larger share of our economy than ever on health care. That in and of itself is concerning, but what is even more troubling is how much of it we are wasting. A 2012 report by the Institute of Medicine estimated $750 billion in waste in the U.S. health care system in 2009 alone…nearly 1/3 of total health spending that year.

That’s right — out of every $3 we spend on health care, we’re throwing $1 right in the trash. Actually, it’s worse than that because many of those wasted dollars on unnecessary treatments have actually cost people their lives.

The responsibility for building a continuously learning health care system rests on many shoulders because the stakes are high. As the IOM committee reports, every missed opportunity for improving health care results in unnecessary suffering. By one estimate, almost 75,000 needless deaths could have been averted in 2005 if every state had delivered care on par with the best performing state. Current waste diverts resources; the committee estimates $750 billion in unnecessary health spending in 2009 alone…

…The entrenched challenges of the U.S. health care system demand a transformed approach. Left unchanged, health care will continue to underperform; cause unnecessary harm; and strain national, state, and family budgets. The actions required to reverse this trend will be notable, substantial, sometimes disruptive—and absolutely necessary.

When we talk about health policy the one area that draws my attention is administrative costs. And, quite frankly, the USA has out-of-control administrative costs largely because our patchwork reimbursement scheme makes things needlessly complex.

In the U.S., there are almost as many different types of health coverage as there are patients. Even within the same insurance company, there are numerous variations from policy to policy. When I worked for a major health insurer, I answered calls from our insurance members but also from physician office and hospital staff who were contacting us just to verify a patient’s benefits, from whether the patient still had insurance to deductibles to coverage exclusions. They had learned that insurance cards weren’t always current or specific enough, so they had to call us one patient at a time because everyone was different…just to make sure they got paid.

Does that sound like an efficient system to you?

It’s a problem they don’t have to deal with in countries with single-payer health systems…like Canada.

Reducing US per capita spending for hospital administration to Scottish or Canadian levels would have saved more than $150 billion in 2011. This study suggests that the reduction of US administrative costs would best be accomplished through the use of a simpler and less market-oriented payment scheme.